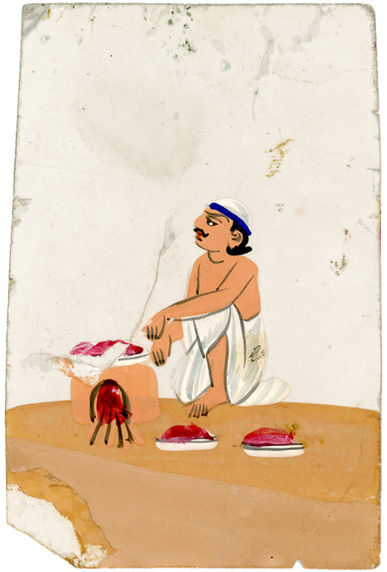

A Measure of Perfection

Writing

Soumitri Debroy

Kishore pulled out a little wrinkled brown notebook (or was it a binding of bills, receipts and tokens of paper one might find littering the desk of a bachelor?) from his right pocket, drew the five-rupee blue ball point pen (one of many he collected through his late night office heists) and violently scribbled thus on page forty-four:

Naryana Dosa Center:

Texture - too crispy

Sambar - too sweet

Chutney - too watery

Masala - potato not cooked enough

3.1/5

He also made a mental note that the waiters here had a streak of arrogance in their eyes and an inkling of Kannada abuses pursed in between their lips, which he didn’t quite like. Narayana Dosa Center cannot be it. Another day, another lunch break laid to waste, he remarked internally. He has spent the last twenty-two days (or is it twenty-five, or thirty, or forty, or a lifetime perhaps?) in the pursuit of the ‘perfect dosa’ in Bangalore. Now, you—a seasoned Bangalorean, forged in its swooshing, warm filter coffee, the indolence birthed by its brisk weather, and an air of agonizing hyperproductivity—might chuckle at the futility of

Kishore’s Sisyphean endeavour. But Kishore has been having sleepless nights (stricken with unnatural anxiety, insomnia creeps out from his forehead like serpentine beads of perspiration), nauseous mornings (he has been skipping his breakfast all this while) and office hours ridden with inattention (he can only bother to care about the lunch break and nothing more). Kishore’s tribulation began on a painfully usual Monday morning when the dosa joint (whose head chef—Kumaran—had once been haughtily proclaimed by him to be a finer cook than his own mother, much to her frantic dismay) he would frequent for his daily breakfast and occasional dinners, decided to exile itself after thirty-eight years of ‘proud service.’ There was not a hint, or an indication of the incoming betrayal—like all things one comes to adore in life, its disappearance too, was absurd. ‘How could they just shut shop? Wasn’t it just last Friday when I tipped Natraj a whole twenty-rupees? Didn’t he remark how customers like me should be more abundant? Was that just a passing remark then? A casual murmur? Nothing of substance?’ Kishore was—this is not an exaggeration—devastated.

For the entirety of the first week, he was utterly loyal in honouring his daily routine and showed up to Amma Dosa Kitchen at sharp 9:15 A.M., banking on every last strand of unreasonable hope in his body, to satiate himself with a plate of ‘Amma’s special podi masala dosa (with extra podi) - Rs. 45’, only to find out that the locks on the shutter wouldn’t have moved an inch and the ‘to rent’ poster would’ve sunken ever so slightly more under fine layers of dust. The following week saw Kishore retract himself into a more pensive disposition—pressing questions about what is to become of his mornings now that Kumaran was gone, lingered.

Concept Note

When I first moved to this city, food was the one thing that made its unfamiliarity bearable. It became my first language of belonging — the comfort at the end of a lonely day, and at times, the sharpest reminder of everything I missed. A dosa could be both home and heartbreak.

“A Measure of Perfection” grew out of that duality. It is, on the surface, a simple story about a man searching for the perfect dosa, but beneath it runs a deeper current of displacement, yearning, and quiet negotiation with a city that often feels both tender and indifferent. Through Kishore’s search, I found myself tracing my own evolution here: how food becomes a bridge, a memory, and sometimes, a measure of one’s place in the world.

It is not just about the dosa, it is about everything the dosa stands for: routine, loss, love, and the fragile ways we find meaning in new beginnings.

Artist Bio

Soumitri is a writer whose works draw equally from the profane and the profound, taking inspiration in life and art alike from sophisticated myths and legends, pulp narrations at family gatherings and house parties, and ‘Che’ Guevara and Mishima. Recently, her works have been stylistically experimenting with Bukowski, Kafka and Camus. When not sleeping and dreaming, she likes to write, read and observe. She likes to spend her time on walks and runs, perusing parks and neighbourhoods, curating cinema and music, and treating herself to Chinese food.